Monty Norman was a Londoner all his life, from his early years in the East End when he lived at his grandparents’ house with his parents Ann (née Berlyn) and Abraham Noserovitch, to his many years as a resident of Maida Vale. His stellar music career meant many trips to LA and New York and even though the American capitals of film and stage were exhilerating and tempting, he always returned to his roots. His home on the western fringes of London was chosen specifically for its road, rail and air links.

Much of what a musician does stems from pivotal points in their life. Success or failure, even changes in the course of music history, sometimes come from the natural progression of opportunities unfolding.

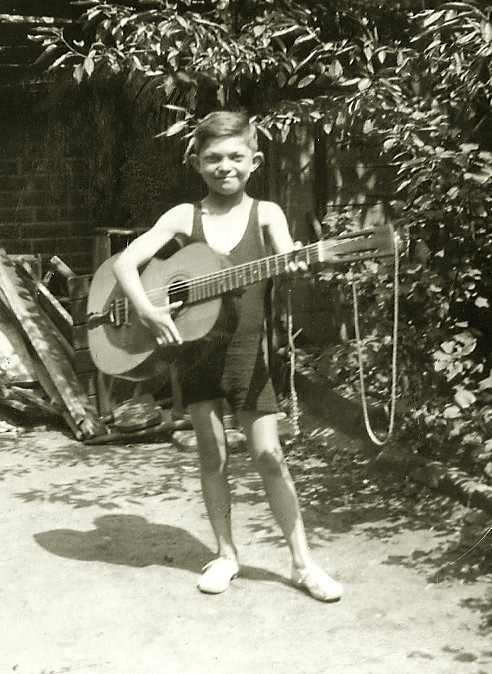

Commenting on a photograph of himself taken in the landlady’s garden,‘That was the first time I had ever held a musical instrument. I can still remember the thrill of the moment.’

Monty’s imagination was fired but while his interest in music was always there, money in the East End of London wasn’t easy to come by. His mother spent hours on her sewing machine making little girls' dresses which her sister sold in the East End markets. His father was a cabinetmaker and both were sympathetic to their only child’s interests.

When Monty was 16 his mother bought him a guitar having knocked the seller’s price down from £17 to £15 – still a small fortune for a working class household.

‘I’ve still got that guitar - a 1930s Gibson. I never use it, but I keep it as a talisman. My mother and father never understood the profession I went on to choose but, bless 'em, they were wonderful and just let me get on with it.’

Monty's uncles were singers with magnificent Gigli-like voices, but financial circumstances dictated they would go no further than amateur opera. Several of their children were also excellent singers, so it did run through the family.

‘I joined the Army Cadets. We used to put on concerts and I suddenly realised I had a voice. Not long after that I started having guitar lessons with Bert Weedon.' Bert became one of Britain's top guitarists. His influence and his popular tuition books helped so many later stars - Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Mark Knofler and Sting, to name a few.

‘During one of my lessons, Bert gave me a left-handed compliment. He said, "Monty, as a guitarist you’ll make a great singer!" He helped me find a first class singing teacher, Laurence Leonard. A friend of Ivor Novello, Laurence wanted me to go into light opera but I had already started doing gigs with young up-and-coming jazz musicians and gave up any pretense of opera.’

Monty began to do radio broadcasts with some of those small jazz bands. ‘It was great fun! Then one of the top band leaders of the day, Cyril Stapleton, heard some of my broadcasts and asked me to join his wonderful sixteen-piece big band. After a great year with Cyril I joined Stanley Black, singing with his big band and his wonderful concert orchestra. We did a Latin American broadcast each week called That Old Black Magic. They were my favourites, together with my Sunday Night London Palladium concerts with the great Ted Heath Orchestra.'

Monty began to do radio broadcasts with some of those small jazz bands. ‘It was great fun! Then one of the top band leaders of the day, Cyril Stapleton, heard some of my broadcasts and asked me to join his wonderful sixteen-piece big band. After a great year with Cyril I joined Stanley Black, singing with his big band and his wonderful concert orchestra. We did a Latin American broadcast each week called That Old Black Magic. They were my favourites, together with my Sunday Night London Palladium concerts with the great Ted Heath Orchestra.'

Monty then became a solo artist singing in weekly variety concerts, broadcasts and television spectaculars. He worked with practically every top comedian of the time. He and Benny Hill did a series of Variety shows together. 'Top of the bill was determined by whether a particular town was more partial to singers or comedians!' Monty laughed.

Monty worked with the Goons, both together and individually with Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan. He also worked with Tony Hancock and Tommy Cooper, among many others.

Then, at what looked like the continuing rise of his successful career as a popular singing star, Monty decided to switch tack and concentrate on writing rather than performing.

‘I had started to write songs and when one of them, False Hearted Lover, became reasonably successful I decided I would like to continue in that direction. My parents had misgivings but I was certain that was what I wanted to do.'

‘I had started to write songs and when one of them, False Hearted Lover, became reasonably successful I decided I would like to continue in that direction. My parents had misgivings but I was certain that was what I wanted to do.'

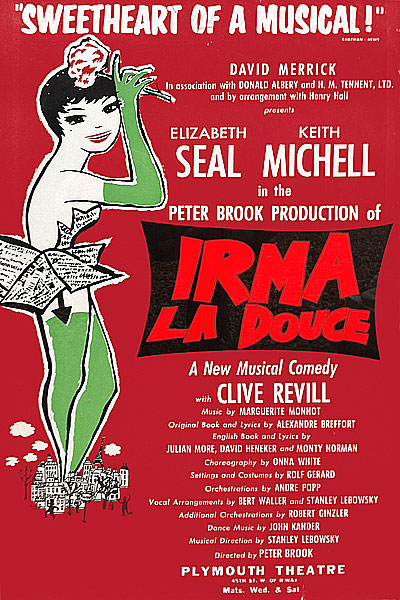

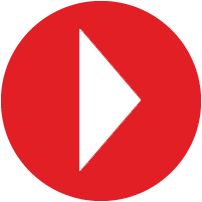

By then Monty had met and started working with Julian More and David Heneker. His new colleagues were some of Britain's top musical talent and included the likes of director Peter Brook and actor Paul Scofield. They were all generous with their time, sharing their knowledge and experience as Monty worked alongside them.

'Within a year we had two major hits in the West End with Irma La Douce and Expresso Bongo.'

Three song extracts from Irma La Douce...

Language of Love

Language of Love

Irma La Douce

Irma La Douce

Dis-donc, dis-donc

Dis-donc, dis-donc

Overture

Overture

The Shrine on the Second Floor

The Shrine on the Second Floor

Nothing is for Nothing

Nothing is for Nothing

Seriously

Seriously

‘As a singer, I loved the stage - I always wanted to play the Palladium and did do some concerts there with Ted Heath. But I also hoped for success with my stage shows and I was fortunate to have that too.’

But he emphasised that while luck plays its part in a successful career, it can never be unaccompanied.

‘Luck happens in the sense that you meet people who are able to help your career move forward. But, as in any sphere, you must have a natural talent combined with commitment and a drive to succeed. There was never a moment when I thought, “I’ve made it” - it has happened in different ways a few times in my career.’

It was while Monty was working with Julian More on a musical based on VS Naipaul’s book A House for Mr Biswas, with the renowned director Peter Brook, that he wrote a song called Bad Sign Good Sign with a strong Indian musical arrangement and instruments. But when casting issues became a problem, the project was shelved. Since Monty had worked on the show as a whole for two years he put the song in his bottom drawer — but didn’t forget about it.

It was while Monty was working with Julian More on a musical based on VS Naipaul’s book A House for Mr Biswas, with the renowned director Peter Brook, that he wrote a song called Bad Sign Good Sign with a strong Indian musical arrangement and instruments. But when casting issues became a problem, the project was shelved. Since Monty had worked on the show as a whole for two years he put the song in his bottom drawer — but didn’t forget about it.

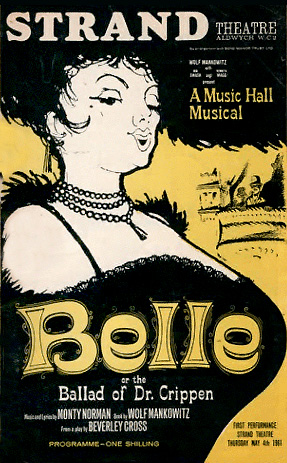

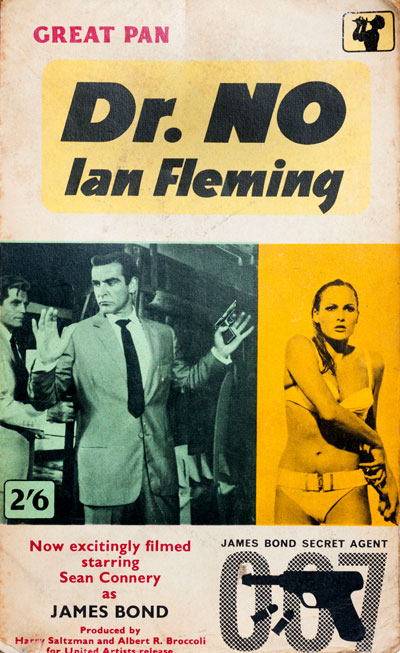

Another show, Belle, about the murderer Dr Crippen, ran for only six weeks (Monty believed the dark subject matter, preceding such shows as Sweeney Todd and Phantom of the Opera, was too challenging and ahead of its time for the  critics). One of the musical's backers, however, was Cubby Broccoli and after telling Monty he had liked the show and would like to work with him again in the future, he remained true to his word. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had bought the rights to Ian Flemming's James Bond novels and asked Monty to work on the score for the film version of the first of them, Dr. No.

critics). One of the musical's backers, however, was Cubby Broccoli and after telling Monty he had liked the show and would like to work with him again in the future, he remained true to his word. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had bought the rights to Ian Flemming's James Bond novels and asked Monty to work on the score for the film version of the first of them, Dr. No.

Nobody at that time could have predicted the Bond films would become such an astutely managed brand, or that they would have such longevity, much less have imagined that the theme tune would become one of the best-known in the business.

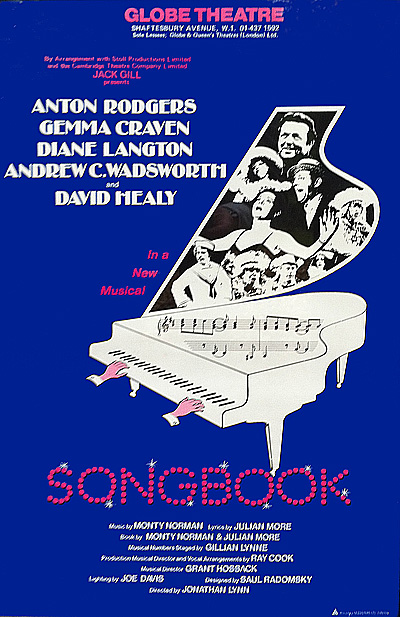

Monty’s stage musical successes continued, among them Songbook which appeared both in the West End and Broadway, picking up Evening Standard, Olivier and Ivor Novello best musical awards and a Tony nomination to boot.

Monty’s stage musical successes continued, among them Songbook which appeared both in the West End and Broadway, picking up Evening Standard, Olivier and Ivor Novello best musical awards and a Tony nomination to boot.

Songbook

Songbook

Don't Play That Love Song Anymore

Don't Play That Love Song Anymore

Nazi Party Pooper

Nazi Party Pooper

His early 1980s musical Poppy, an innovative pantomime-style production, ran for over a year at the Barbican Theatre and the Adelphi Theatre, and was awarded the SWET (Lawrence Olivier) best musical and nominated for the best musical category in the Ivor Novello awards.

Monty's work has featured in the recording output of many other artists and performers including Cliff Richard, Tommy Steele, Paul Scofield, Count Basie, Jack Jones, Bob Hope, Shirley McClaine, John Barry Seven, Moby and others.

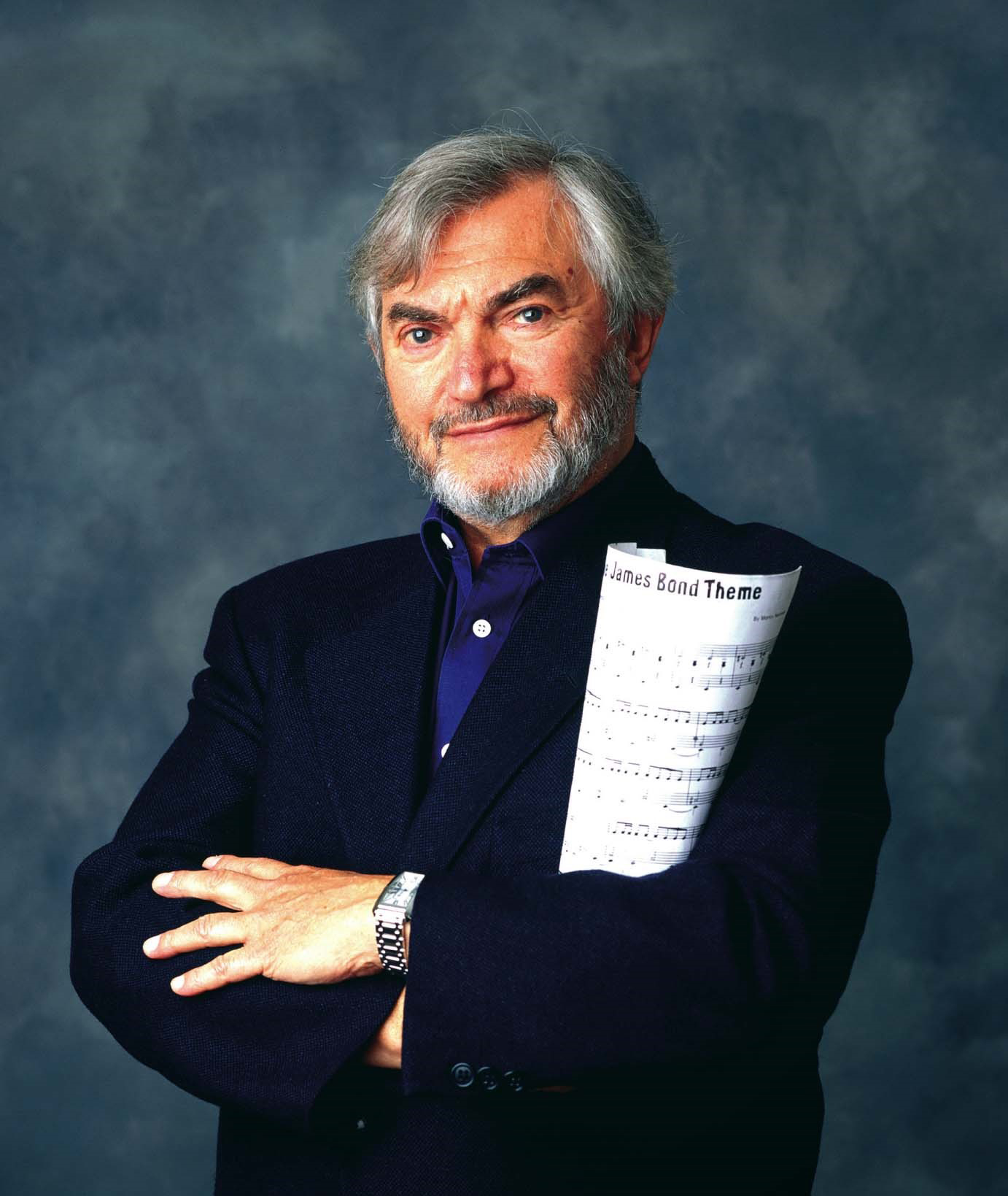

In addition to the music for Dickens of London, Monty was involved in the TV scores for Who Is Sylvia?, The Battersea Miracle, Fly on the Wall, A Bit of Discretion, Make Me An Offer, Quick Before They Catch Us and others. His film music output is also notable for the Bob Hope feature Call Me Bwana and the Hammer film The Two Faces of Doctor Jeckyll. Of course, The James Bond Theme will continue to make a huge contribution in every Bond film yet to be made.

In his nineties, Monty Norman might have been forgiven for taking it easy, but far from resting on his laurels he became enthused about a new project, an animated film.

In his nineties, Monty Norman might have been forgiven for taking it easy, but far from resting on his laurels he became enthused about a new project, an animated film.

‘It’s a big project and everyone who has had a smell of it seems to like it.'

Mississippi Big is a story set in the world of birds in the Mississippi Delta.

‘It’s something I’ve created entirely, the characters, the dialogue, the songs. I’ve just about finished the first draft and top animation studios will be seeing it shortly.'

Thinking about why he was still writing and working so hard, Monty said he still had plenty of ideas and had no plans for absolute retirement.

‘As a writer with numbers or shows that keep coming back, you never stop. I didn’t expect myself to be writing something as complete as Mississippi Big, but it was almost organic - it slowly grew and it’s been fun to do. With films, you never quite know what’s going to happen but I’m sure it will be a very good film and people who know what they’re talking about agree. We’ll see. I’m excited because it’s something different for me.'

‘Well, I hope when the time comes people will remember that I’ve done quite a few things, but the fact that James Bond is so iconic in everybody’s mind - you can’t argue with that and nor would I want to.’

Inevitably that time did come. On the 11th of July 2022 Monty's family shared the sad news that he had died after a short illness. The many international press and media features and tributes that appeared that day showed he needn't have worried about the breadth and variety of his achievements being remembered. But his ongoing legacy will of course be 'that tune' - a gift to cinema history that will surely continue to thrill generations to come.

Based on an interview with Sandra Kessell